Early Refrigeration Only in Large Homes

The refrigerator is so commonplace today we scarcely notice its presences in our homes. But when it first appeared, its social effects were wide-ranging.

To begin with, home refrigeration was a luxury. Only the owners of the largest homes typically were able to afford the new convenience. And only the largest homes had the space to accommodate a technology that was at first little modified from its commercial and industrial precursors.

A Practical Home Refrigerator

Household refrigerators became practical as soon as it was possible to combine refrigeration machinery and a cooling unit in a single cabinet. The big breakthrough in bringing refrigeration to the home was the development of the unitary refrigerator. By ‘unitary’ is meant an appliance that combined all the equipment necessary to cool food together in a single cabinet. This innovation was to become one of the most influential new household appliances of the twentieth century, the home refrigerator. The unitary cabinet refrigerator could be used as an instant replacement for the ice box. No complex installation – no need to reserve a lot of space for refrigeration. Just plug it in, and it could stand in the kitchen where the old ice box had stood.

Fresh Food for Longer … Refrigerators did a better job of keeping food fresh than an ice box.

The most important single advance in the kitchen was reliable temperature control. As long as the power stayed on and as long as the refrigeration machinery did not break down, the food stayed cold. The refrigerator achieved food storage temperatures that were lower than those experienced on average with the ice box. And those temperatures were constant. Perishable foods could be kept fresh, appetizing and nourishing, right in the kitchen, for much longer than had ever been possible before. The potential effects on nutrition were obvious.

Constant Cold, at Fingertip Control … The temperature control, or thermostat, put the in control of food storage temperature.

Though we are familiar with today’s technology, and as the first refrigerators entered the home, the emergence of a thermostat-controlled ice box must have seemed almost magical. Just twist the knob in one direction, and the temperature went down. Twist in the opposite direction, and the temperature in the refrigerator went up again.

The refrigerator’s thermostatic temperature control, a self-regulating device, put this new appliance in the same league as that other marvel of early twentieth century engineering, the automobile. Just adjust the accelerator and the vehicle speeded up. Step on the brake and it slowed down again.

The thermostat incorporated technology that made it possible to determine the temperature in the food storage chamber and to activate a switch that turned on the refrigerator’s motor when that temperature got too high. After the compressor had run for a while and the chamber cooled off again, the power was switched off. The temperature at which this switching occurred is called the set point for the thermostat and was adjusted higher or lower by twisting the temperature control knob.

Chilled Luxuries at Home … The refrigerator made it possible to keep ice cream at home and make ice cubes for chilled drinks.

In addition to keeping perishable foods fresh, the refrigerator could do things not even dreamed of with an ice box. The low temperatures that could be achieved within the coils of the cooling unit, called the evaporator, made it possible even to make and keep ice cream frozen for weeks.

The evaporator came to be called the freezer, because the homeowner could put a tray of water into it and take the tray out a few hours later full of ice. This was new ice, artificial ice, ice you could make in your own home.

Refrigerator manufacturers were the first to realize what an amazing product they had on their hands. Yet like any new technology, acceptance was slow at first. Most people are slow to give up things they are familiar with to adopt new and unfamiliar things, especially during the depression years when money was scarce.

So the manufacturers set out to communicate all of the benefits of this new technology in order to convince householders to buy it. These new treats, the iced drink, and ice cream sundae at home, seemed like the obvious way to start.

Quality construction and reliability were stressed as a selling point for early refrigerators.

Buyers of the times were quality conscious. To make the early refrigerator acceptable to consumers, manufacturers had to clearly demonstrate quality through solid construction and reliability. The gleaming, white enamelled exterior finish distinguished this new, metal-clad appliance from the old wooden ice box and reflected a new definition of quality.

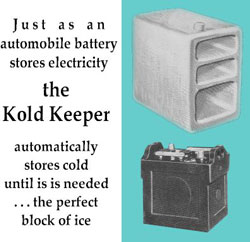

Like Ice, Only Better … Early refrigerator advertising stressed the similarities to a block of ice.

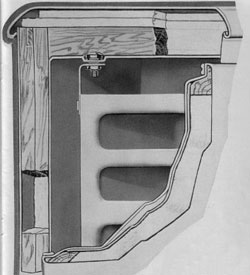

Not only the appearance of the refrigerator was unfamiliar, but no potential buyer had the faintest idea how it worked. The only familiar way of cooling food was using a block of ice in the ice box. So, the cooling unit (evaporator), the visible centre of the refrigerator’s cooling effect, was first manufactured to be similar in size and shape to a block of ice. Consumers could look inside the new appliance and imagine that the ‘thing’ that kept the food cold was just a kind of mechanical block of ice.

While heat can be stored, cold is just an absence of heat. The concept of storing cold is not consistent with the theory of heat. But it was a popular notion, and the advertisers took advantage of this. The idea of storing electrical power in a lead-acid battery had become familiar with the more widespread use of automobiles. In the popular mind, a block of ice ‘stored’ winter’s cold until it was needed on a hot summer day. So, the refrigerator’s cooling unit, or freezer, was promoted as storing cold like an automobile battery stores electricity, like a block of ice stores cold.

Notice that the evaporator was also similar in size and shape to an automobile battery. Some early cooling units incorporated a hollow jacket containing a brine solution. The brine solution was cooled by the evaporator and continued to absorb heat, even when the refrigerator was not running. Thus, the capacity to cool was maintained, or ‘stored’, much as the advertisement claimed.

The Efficient Kitchen … Advertising of the 1920s and 1930s pointed out the efficiencies the refrigerator.

The unitary cabinet refrigerator could be reduced in size so that it eventually took up less space than the ice box. You could fit it into a compact space that included a stove, a sink and cupboards to store food and tableware. It only took a few steps from refrigerator to food preparation counter, and then on to the stove.

Food could be kept longer so daily runs to the market were unnecessary. Cooked food that was not needed for this evening’s meal could simply be stored in the refrigerator and used again for another meal. The age of leftovers had arrived. It was even possible now to cook enough food at one time for several meals and store the excess in the refrigerator.

The notion of kitchen efficiency was borrowed from the early twentieth-century efficiency movement in industry. The theory held that industrial productivity could be increased if every job performed on the factory floor were performed in a standardized way, with the fewest possible movements in the least time.

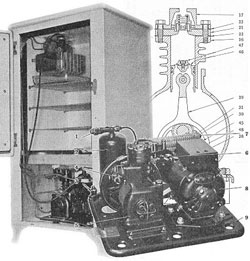

The first refrigerators were noisy, required frequent servicing and contained a noxious refrigerant.

Despite the glowing promises of the advertisers, early household refrigerators were far from perfect. The appliance still had several qualities that made it hard for consumers to adopt it without reservation.

The system was subject to frequent leaks of the refrigerant gas. And mechanical parts, such as the motor, belts, and pulleys, required frequent servicing. A drop of oil here, an adjustment there.

Motors needed to be oiled every three to six months; drive belts had to be regularly replaced; compressor parts needed to be removed; while ground smooth at the same time as seals were replaced. And the constant vibration would eventually crack the copper pipes used to circulate the refrigerant.

Engineering departments of the major manufacturers were working hard to overcome some of these limitations. But the difficulties were completely ignored by the advertising department, which simply redoubled its efforts to promote the new appliance’s benefits and stimulate further sales.

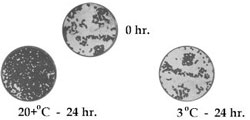

Preserving Food from Microbial Contamination

Selling refrigerators involved demonstrating the benefits of keeping food at a constant low temperature.

Because of some of the problems of early refrigerators, the consumers required plenty of convincing. One argument that few could resist however, was for the improved quality of food stored in refrigerators. To make their case, advertisers called upon the fledgling science of microbiology.

By the early twentieth century, the microbial nature of disease was widely appreciated. Refrigerator manufacturers took care to stress as well that it was microorganisms, microscopic fungi and bacteria, that were responsible for the spoilage of perishable foods.

Using microscopic views of the multiplication of food spoilage microorganisms, it was easy to show that food could be kept safely for 48 hours or longer under conditions of mechanical refrigeration. The ice box, however, with its higher average internal temperature could barely keep food fresh more than 24 hours.

No one wanted to expose their family to the unpleasant odours and health hazards of spoiled food. Letting food spoil was wasteful and expensive. What could be more desirable then, but a new refrigerator to prevent all this unpleasantness from happening?

No More Paying for Ice

Salesmen claimed that the new refrigerators saved money on buying ice.

Not only did the owner of a brand-new refrigerator save money by avoiding spoiled food. They didn’t have to buy ice for it either.

Yes, economical operation was a strong selling point for home refrigeration technology. Electrical power was inexpensive and widely available, and besides, the home owner in the 1920s and 1930s was unlikely to be aware if a refrigerator used more power than light bulbs or not.

Cooling Off on a Hot Day … Life at home was more comfortable than ever before.

Advertizers started to incorporate convenience and comfort into their sales incentives.

Refrigerators made for less work in the kitchen, so life was more comfortable. You could cool off right away with an iced drink, or an ice cream cone. Recipes were offered for various kinds of chilled desserts – gelatine moulds, parfaits, sundaes, sodas, frappes, sorbets – the prospects were mouth-watering.

Unheard of Choice and Convenience … The refrigerator had stimulated greater food diversity in the marketplace.

With a dependable source of cold storage to keep foods fresh longer, consumers had a greater of food options. the refrigerator made greater choice in diet possible. Food producers responded to the demand. The result was the production of greater varieties of perishable food than ever before.

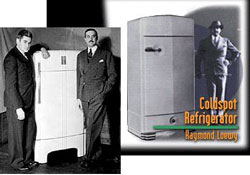

The Refrigerator – An Object of ‘Modern’ Beauty

By the 1930s, refrigerator manufacturers were using designers to make the machines more ‘modern’ and aesthetically pleasing.

To sell more refrigerators, manufacturers soon realized that they had to get away from the ice box image. Mechanical refrigeration was a radical departure from the ice box, and its capacity to change home life was unique. It was time, finally, to escape the comforting similarity to the earlier appliance that had been so crucial to early acceptance.

Design changes were going on everywhere. For example, the Sears Company retained the famed industrial designer Raymond Loewy to re-design their top selling Coldspot refrigerator’s appearance.

All That is Modern

Coined in the 1920s and used widely in the 1930s, the term modern soon became synonymous with all the potential that people dreamed of for the twentieth century. It symbolized the triumphs of technology in giving more control over the world and creating better lives.

Modern had a visual style too. It was symbolized by simple geometrical forms and plain undecorated surfaces. Modern designs often incorporated flowing curves; an effect referred to as streamlining. Not surprisingly, refrigerators were streamlines to appeal to evolving consumer tastes.

Ice … New Lifestyles – On Demand

In the ever more ingenious search for ‘selling features’ advertisers focused on lifestyle. A new refrigerator would change your life. It could make you more comfortable, more sophisticated, more modern. Great creativity went into making ice cube trays easier to use so that the refrigerator could become an endless supply of these convenient little chunks of concentrated cold.

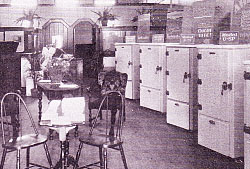

The Creation of Desire

Refrigerator manufacturers advertised hard to create the desire for a refrigerator in every home, the latest model with the most features.

By the 1930s the passion for all things modern had been carried even to small town Canada by savvy marketers. Advertising stimulated public demand for the latest, the most modern appliances and other manufactured products.

Refrigerator manufacturers not only applied modern styling to their appliances, but they also created new models every year or two to cater to an increasing demand for the very most up-to-date household conveniences. A new refrigerator made consumers feel like a part of twentieth century progress.

Unknown Needs May Be No Less Real

Advertizing for refrigerators may have created the desire to purchase, but consumers soon found they needed the new appliances.

New Goods and Services for The Home

By the early 1930’s it was clear that new economic infrastructures were developing for production, sale and transportation of new taste delights and other life amenities (like cut flowers) for the home.

Industrial refrigeration had been available longer than refrigeration in the home. But until the demand for more perishables appeared at the consumer level, refrigerated industrial facilities were not in great demand. This changed rapidly as home refrigerators spurred an appetite for delicacies, like seafood, that were previously unimaginable. Refrigerated transportation made getting this product to market more effective than ever.

A New Era of Food Production

Refrigeration allowed for improved quality control in the production of perishable commodities such as dairy products.

With mechanical refrigeration increasingly playing a role on the farm and in the milk distribution plant, the dairy products industry was producing and delivering higher quality products than ever before. Milk could now easily be protected from spoilage microorganisms. And the process of pasteurization was now widely required to protect against transmitting disease organisms via the milk supply. Advances in dairy science meant that it was possible to analyze the microbial content and chemistry of milk at every stage in its production. These analyses and the ability to retain milk quality during storage and delivery meant that very high standards could be met.

Expanding Retail Sales

Refrigeration led to expanded demand for perishable foods as well as the capacity for retailers to stock a greater variety.

Meat, cheese and fish had been sold in small shops for many decades. Without refrigeration, however, such operations remained small, and stocks limited to a day or two. New commercial refrigeration units enable small merchants to stock more products, increase sales and grow from small to medium-sized operations.

Enhanced Transport of Perishable Goods

Refrigeration equipment could be installed in delivery trucks, making it possible to transport perishable products for long distances.

Commercial refrigeration equipment developed for food stores and warehouses could be easily adapted for installation in a truck too. The main innovation required was the provision of power to the compressor. Truck mounted refrigeration units could be powered by a separate motor driven by diesel or other fuel, or by direct electrical current generated by the vehicle’s electrical system.

International Transportation of Perishable Foods

In the early twentieth century the greater part of transcontinental transportation of products and commodities was by rail. Limitations in highways and the reliability of trucks over long distances meant that transportation by road was largely local or regional.

Railways had long dominated the inland transport of durable goods and commodities, such as coal and wheat. Refrigerated freight cars made it possible to carry perishable products for thousands of kilometres.

The Kitchen and The Abundance of Things

The refrigerator was only the start of the modern appliances that would soon be needed in the kitchen. A greater focus on the home kitchen and all the new conveniences it could produce meant the development of many new products for cooking and food preparation.

Since early in the industrial revolution there had been many manufactured examples of kitchenware – baking dishes, casseroles, serving platters and so on. But many more for handling ice, refrigerated beverages and a variety of refrigerated desserts, were now added to these.

The kitchen stove also began a process of technological evolution. And by the 1930s a proliferation of small electrical appliances like blenders and food mixers appeared.

A New Richness of Commodities in the Kitchen

As refrigerators became commonplace, the kitchen became part of the culture of abundance – the abundance of commodities and services. Most homes could now afford to keep a wide range of food products.

Locally produced fruit was joined by citrus fruit produced in sub-tropical regions. Perishable vegetables like lettuce and broccoli became available for longer and longer periods of the year, not just during the immediate local growing season.

An Improved Quality of Life

Through the development and marketing of household and consumer technologies, small town Canadians were living healthier, better nourished lives.

Small towns flourished and citizens prospered. The increases in commerce meant that more and more products and services could be found in small centres as well as cities.

Availability of more products stimulated demand, and the consumer society was born.

Food and Agriculture Industries

Through the development and marketing of household and consumer technologies, agricultural trades were becoming food and agricultural industries. Refrigerated shipment and cold storage meant that agricultural industries could benefit increasingly from centralization and economies of scale.

Milk production, for one, was amenable to packaging, handling, and marketing methods that had already been developed in the manufacturing sector.

The production line model came to be widely used. And small, local businesses – dairies, butchers, grocers – were crowded out by their larger, more centralized, and more industrialized competitors. The food chain stores quickly followed.